The Euro involves:

- A single currency within the Eurozone area.

- A common monetary policy. Interest Rates are set by the ECB for the whole Eurozone area.

- Growth and Stability Pact. In theory there are limits on government borrowing, national debt and fiscal policy. However, in practice member countries have often violated the strict limits on government borrowing.

Problems and costs of the Euro

- Interest rates not suitable for whole Eurozone. A common monetary policy involves a common interest rate for the whole eurozone area. However, the interest rate set by the ECB may be inappropriate for regions which are growing much faster or much slower than the Eurozone average. For example, in 2011, the ECB increased interest rates because of fears of inflation in Germany. However, in 2011, southern Eurozone members were heading for recession due to austerity packages. The higher interest rates set by the ECB were unsuitable for countries such as Portugal, Greece and Italy.

- The Euro is not an optimal currency area. If a state in the US, such as New York ,was in recession, workers in New York could move to New England and get a job. However, in the Eurozone this is much more difficult; it involves moving country and possibly learning a new language. There are more barriers to the movement of labour and capital within a diverse region like Europe. Therefore, an unemployed Greek can't easily relocate to Germany. see: Two Speed Europe

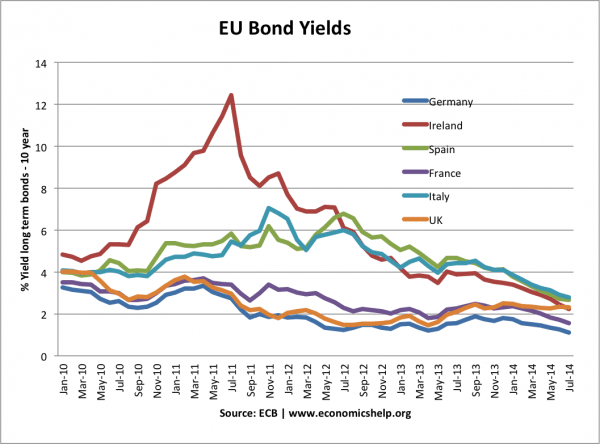

- Limits Fiscal Policy. With a common monetary policy it is important to have similar levels of national debt, otherwise countries may struggle to attract enough buyers of national debt. This is a growing problem for many Mediterranean countries like Italy, Greece and Spain who have large national debts and rising bond yields.

- Lack of Incentives. It is argued that being a member of the Euro protects a country from a currency crisis. Therefore, there is less incentive for countries to implement structural reform and fiscal responsibility. For example, in good years Greece was able to benefit from very low bond yields on its debt because people felt Greek debt would be secured by rest of Europe. But, this wasn't the case, and Greece were lulled into a fall sense of security.

- No scope for devaluation. Since the start of the Euro, several countries have experienced rising labour costs. This has made their exports uncompetitive. Usually, their currency would devalue to restore competitiveness. However, in the Euro, you can't devalue and you are stuck with uncompetitive exports. This has led to record current account deficits, a fall in exports and low growth. This has particularly been a problem for countries like Portugal, Italy and Greece.

This shows the effects of Eurozone members becoming uncompetitive. Very high current account deficits.

- No Lender of Last Resort. The ECB is unwilling to buy government bonds if there is a temporary liquidity shortage. This makes markets more nervous about holding debt from eurozone economies and precipitates fiscal crisis. See: Problems of Italy - why Italian bonds increased despite having a much lower budget deficit than UK.

- However it is worth noting that since Mario Draghi took over and promised to 'do whatever it takes, the ECB has effectively acted as lender of last resort.

Italy bond yields rose despite a primary budget surplus

- Deflationary Bias I would argue there is a deflationary bias in the Eurozone which increases the risk of recession and higher unemployment

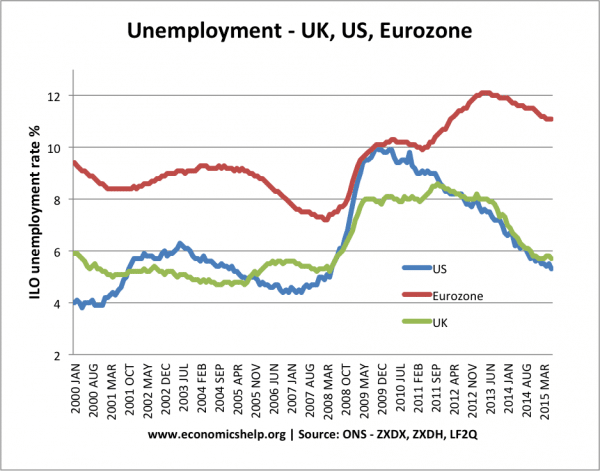

Eurozone members have seen a rise in unemployment - higher than US and UK

- Divergence in bank rates. In theory, the Eurzone creates a common interest rate. However, in the credit crisis of 2010-13, we see rising bank rates for peripheral Eurozone countries, like Italy and Spain. Small and medium sized firms faced higher borrowing costs than in 2005, even though the ECB cut the main base rate. This suggests that the ECB was unable to loosen monetary policy when needed. See more on credit policy

- Asymmetric Shocks. If one country experienced an external shock it might need a different response. But this is not possible with a common currency. E.g. German reunification required higher interest rates in order to help reduce inflation but this was not good for many other countries.

- An oil shock would affect net importers like France more than Norway and the UK who export a lot. Monetary Policy will have different effects in different countries. For example, the UK is sensitive to changes in the interest rate because many people have mortgages.

Experience of EU Fiscal Crisis

The great recession of 2008-11 showed the vulnerability of Euro member countries to a common monetary policy. Because they can't devalue and also ask the Central Bank to buy government securities they are at much greater risk of a liquidity crisis.

Because of fears over liquidity crisis, bond yields rose from Ireland, Spain, Portugal and Greece. As a result these eurozone countries were forced into pursuing spending cuts, and accepting higher interest rates. But, this led to a vicious cycle of lower growth and lower tax revenues.

See: Why UK bond yields stayed low compared to Euro members

Problems for UK Economy

UK economy has additional problems which make joining the Euro a bad idea.- Housing market. Many in the UK have a mortgage which is a big % of their disposable income. This is related to the high cost of buying houses in the UK.

- Variable Mortgages In the UK more homeowners have variable mortgages. These two factors means UK consumers are very sensitive to changes in the base rate. If the ECB kept interest rates higher than the UK needed it would create serious problems in the UK. Arguably to join the UK would need to reform its housing market and reliance on variable mortgages.

No comments:

Post a Comment