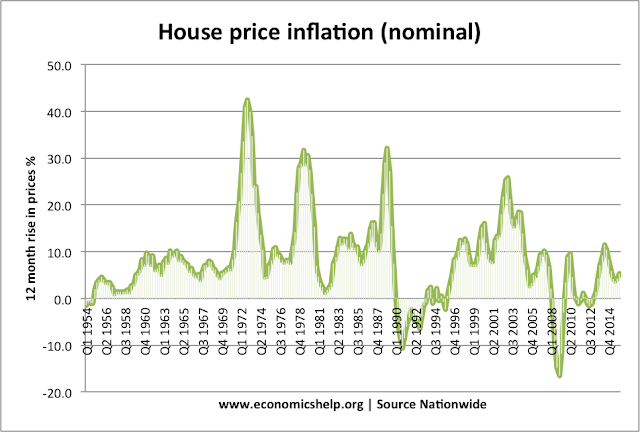

- House prices are volatile with frequent booms and busts.

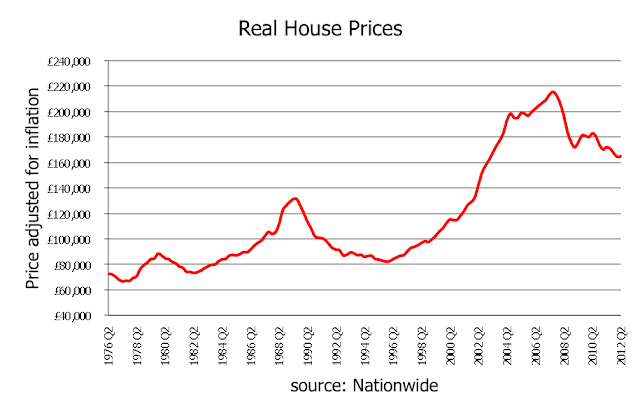

- Despite volatility, and even adjusted for inflation - UK house prices have been on a strong upward trend since the 1930s.

Main factors affecting house prices

- Supply. UK house prices have stayed relatively high (despite recession and credit crunch) because of a shortage of supply. Ireland and Spain have seen much bigger house price falls because they have large excess supply.

- Interest rates. The UK housing market is sensitive to changes in interest rates. Higher interest rates in the early 1990s made mortgages unaffordable and caused a big drop in house prices.

- Economy / unemployment. A recession and rising unemployment usually causes lower demand for buying houses and a fall in price. (falling house prices also tend to deepen the recession)

- Mortgage availability. In the boom years of 2000-07, banks were keen to lend and they relaxed their lending criteria, enabling more people to get a mortgage. But, the credit crunch meant banks had to tighten their lending criteria making mortgages difficult to get (even though interest rates were low)

- see more at: factors affecting housing market

Why are UK house prices so volatile?

UK house prices have been highly volatile in the past few decades. On the one hand this is unexpected. People don't buy and sell houses like a commodity. But, in practise, house prices are volatile for a number of reasons.

- Inelastic supply. It takes time to build houses - with rising demand, supply often can't keep up. This pushes prices up.

- Change in credit conditions. Mortgage availability can vary depending on the state of the banks and financial markets.

- Changing interest rates. Interest rates are used to control inflation, but a rise in interest rates has a big effect on demand and affordability.

- Changes in confidence. In the boom years, we see landlords buying to let and demand rises. When prices fall, people don't want to buy for fear of negative equity.

Why are UK house prices so expensive?

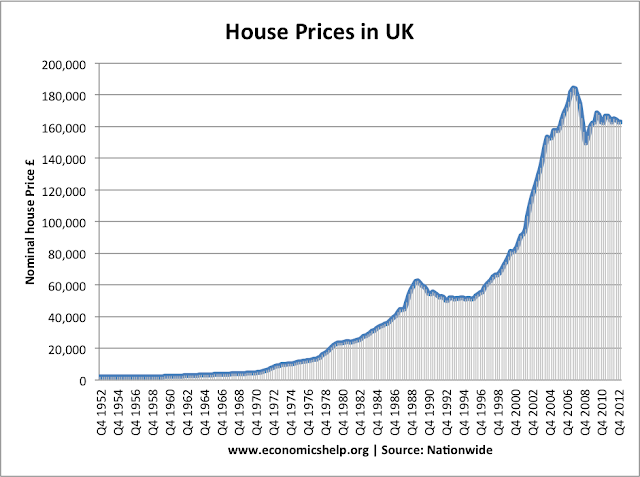

(graph showing nominal house prices)

UK house prices are very expensive. Despite the credit crunch, UK houses are still less affordable in 2013 than at the end of the Lawson boom in the 1980s.

If we look at the affordability of mortgage payments, buying a house looks more affordable because interest rates are much lower in the 2010s, than in the 1990s. But, with house prices nearly 7 times average earnings in London, buying a house is out of the question for many first time buyers. Generally, mortgage companies only lend 3-4 incomes. It is too difficult to raise a deposit. Why are house prices so expensive?

1. Demand rising faster than supply. The UK fails to build enough houses to meet growing demand. This is related to strict planning legislation and the frequent local opposition to building new houses. Home building was also hard hit by the credit crunch. See more at Supply of houses

Housing market crashes

If the UK had a boom in housing builds, we may have had a similar experience to Ireland. In the boom years, Irish house prices rose 300%, but between 2006 and 2012, house prices collapsed, falling more than 50%. The main difference is that Ireland were building record numbers of houses, leaving a glut in the property market. Irish boom and bust. See also boom and bust in US housing marketHow does the Housing market affect the rest of the economy?

Housing is the biggest form of personal wealth in the UK. Changes in house prices have a significant effect on UK household wealth and confidence. If house prices are rising, homeowners can gain extra cash through re-mortgaging their house and spending the extra equity (this was a feature of the 1980s and 2000s boom). Therefore, rising house prices tend to increase consumer spending. However, if people see falling house prices, they lose capacity to re-mortgage and also consumer confidence tends to fall, leading to lower spending. Falling house prices in 2009 and 1990 were key factors in contributing to the recessions of those periods.see more at: Housing market and economy

Government intervention in the housing market

Ideally, the government would overcome market failure in the housing market. This would involve:- Increasing supply to overcome fundamental shortage.

- Protecting green belt land

- Ensuring minimum standards of house building and ensuring tenants get a fair deal

- Seeking to avoid house price volatility.

Related posts on the housing market

2 comments:

I cant seem to comment on article so emailing. I enjoy your blog, wanted to comment on part of your housing supply article....

While I agree with most of your assertions in this and other blogs, I’d comment on the aspect of housing land supply and planning legislation. It is true that the planning system provides supply; but local authorities must ensure that development plans provide an effective supply of housing land, and will be penalised if they don’t (i.e. if they don’t plan for new houses, they will lose appeals for refused planning applications from house builders), and this performs an automatic regulatory function for the planning system. Whether this framework was enough to satisfy demand in boom years is another matter; however, the economic downturn has changed the profile of meeting housing demand, and I don’t believe it currently constrains supply, for the following reasons:

· Demand is quantified by research/monitoring processes and strategically planning for housing, and this is still quantifiable, and suggests there is demands and needs for houses.

· However, land values have not lowered so house builders must still pay a premium for sites they don’t own, while they also must plan longer to build-out, and sell houses on a development site (hence, longer borrowing period to fund development and higher interest costs). This means that new houses remain at an over-inflated price. They are forced to retain new build houses at an unrealistically high value. They have to incentivise to sell (i.e. part-exchange, shared equity), which are really schemes to trap buyers (often first time buyers) into buying a house at a significantly over inflated value – they’ll instantly be in negative equity, possibly with further debts to repay to the house builder. What local authorities now find in trying to plan for supply is that there is still an expectation to supply land for new houses; but large portions of the existing supply of land they have (i.e. sites that have permission, and have already passed through the system) are not being built by house builders because they can’t sell at the same rate. They still want more sites, though. This is because i) they can choose easier-to-develop sites (i.e. those with low development costs i.e. providing less infrastructure) and ii) they can land bank and drip-feed supply, to retain high land value, constrain supply and hold higher house prices to retain profits margins at the highest possible level.

· For second-hand houses, while there is the same high demand, it is now inaccessible because the housing chain has been massively broken because first time buyers can’t get on the ladder because of access to credit, and consequently second time buyers being unable to sell and often have low equity in houses so can’t afford to drop asking prices, substantially. There has been some fall in prices, but much less than in Ireland and Spain, as you mention – but because of these factors, the market has probably bottomed-out, and there is unlikely to be a significant further fall in prices. Since prices are now as low as they’ll probably be, those that benefit are generally people who bought a long time ago and have massive equity in their property, who can either afford to sell at a lower value to get a better property at the lowest relative value it will have (or will have had) for some time; or those that have excess cash or huge equity that can afford to buy-to-let, knowing their investment, isn’t likely to significantly devalue. It will not be first time buyers or second time buyers, who have a more direct need for housing.

While there often is opposition to new houses, and this can slow the system a bit, it can’t, in itself, result in denying planning permission for new houses. This is not a major factor.

Thanks for uploading above comment! Just a few additional points... To clarify, objections are relevant, but only if they raise genuine planning objections. 99% of planning objections should be picked up anyway by the local authority.

plus, Excuse the typos etc. Typed on my mobile. Neale

Post a Comment